-

Anti-GMO Groups Exploit COVID-19 to Block Access to Biotech Crops

Fri Nov 20 2020. 2 min readAs always, the poorest of the poor will suffer most

by Kathleen L. Hefferon and Henry I. MillerThe COVID-19 pandemic continues to take its toll on our lives in so many ways, including diminished social contact, disrupted commerce, and neglect of routine preventive healthcare. One unobvious example has been interruptions in various links in worldwide food supply chains, from farmers' markets to large food manufacturers. For some countries, heightened attention to the development of coronavirus vaccines has indirectly delayed the regulatory approval and adoption of important new crop varieties developed via new breeding techniques (NBTs), such as genetic engineering (also known as "genetic modification," or "GM") and genome editing.

(The whole spectrum of definitions for breeding techniques is arbitrary. We don't find terms like "transgenesis" or "genetic modification" useful or use them, because, for example, performing a wide cross hybridization yields a transgenic organism, by definition, but some people would limit transgenesis to the use of NBTs. Putting it another way, we would say that "transgenesis" refers to a result, independent of technique.)

By limiting the access to new, improved crop varieties, these disruptions negatively affect the farming productivity and food security of poorer nations, such as those in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

COVID: A new excuse to attack Golden Rice

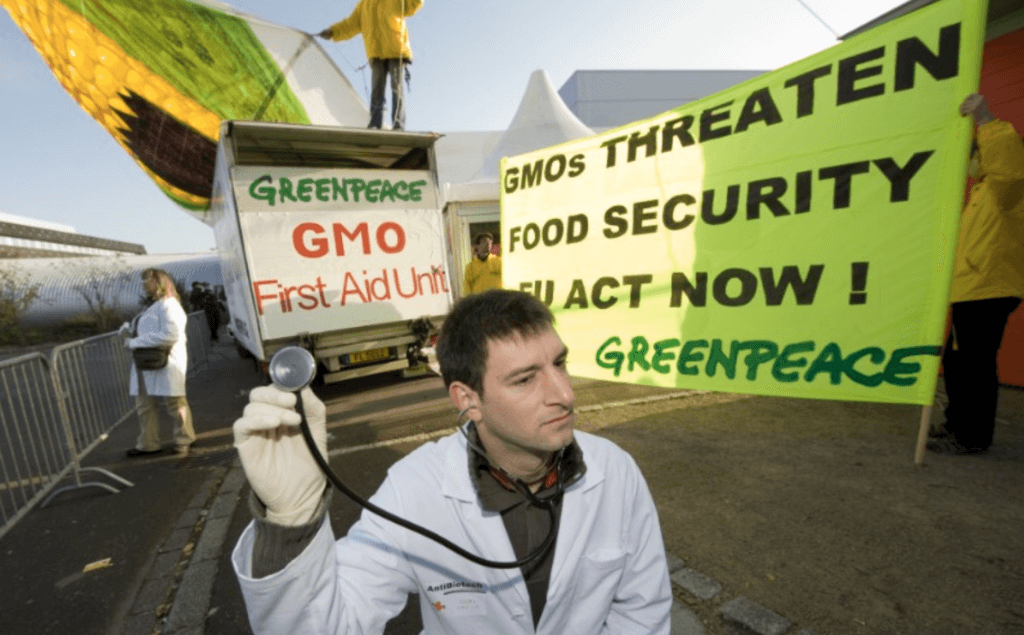

The connection between vaccines and food might seem obscure, but anti-science, anti-technology activists have been ramping up efforts to exploit the pandemic, conflating concerns about vaccines with anti-biotechnology propaganda. Groups such as the Stop Golden Rice Network and Greenpeace have campaigned against the release in the Philippines of Golden Rice — groundbreaking, vitamin A-fortified rice varieties — falsely claiming that multinationals are profiteering during the pandemic, in spite of the fact that Golden Rice has always been a philanthropic endeavor. This mendacity is nothing new: Greenpeace and other activist groups have been conducting a cynical and sometimes criminal campaign (vide infra) against Golden Rice for decades.

Rice is a food staple for hundreds of millions, especially in Asia. Although it is an excellent source of calories, it lacks certain micronutrients, such as vitamins, necessary for a complete diet. In developing countries, 200 – 300 million children of preschool age are at risk of vitamin A deficiency (VAD), increasing their susceptibility to infections such as measles and diarrheal diseases. Every year, about half a million children become blind as a result of VAD, and 70 percent of them die within a year of losing their sight.

In the 1980s and 1990s, German scientists Ingo Potrykus and Peter Beyer developed the Golden Rice varieties that are biofortified by the introduction of genes that enable the edible endosperm of rice to produce beta-carotene, the precursor of vitamin A. Rice plants normally produce beta-carotene in the leaves but not in the grains, so Potrykus and Beyer inserted two genes – one from a bacterium, the other from corn — causing beta-carotene to be synthesized in the edible part of the plant as well. More recently, a gene-edited counterpart to Golden Rice has been developed that does not incorporate genes from other species.

It is difficult to comprehend the extremes activists will go to, in order to undermine something as benign and life-saving as Golden Rice and prevent it from reaching those whose lives are threatened by vitamin A deficiency.

Given its ability to prevent the scourge of VAD, Golden Rice could make contributions to human health on a par with the Salk polio vaccine, but irrational, self-interested, relentless opposition to the testing and widespread availability of Golden Rice has been high on the agenda of activist groups like Greenpeace, a hugely wealthy behemoth with offices in more than 40 countries, and whose PR machine is focused on denying millions of children in the poorest nations the essential food nutrients they need to stave off blindness and death. They have intimidated government officials by fomenting faux-grassroots opposition to regulatory approvals of Golden Rice and other genetically engineered crop varieties; and, as a result, too often, regulators have dragged their feet or capitulated.

Greenpeace has fiercely opposed genetic engineering applied to agriculture from the early days of molecular genetic engineering — recombinant DNA technology, or "gene-splicing," to produce so-called GMOs. In 1995, the organization announced that it had "intercepted a package containing rice seed genetically manipulated to produce a toxic insecticide, as it was being exported . . . [and] swapped the genetically manipulated seed with normal rice." [I. Meister, "Uncontrolled Trade in Genetically Manipulated Products," press release, April 7, 1995].

The rice seeds stolen by Greenpeace had been genetically improved for insect resistance and were en route to the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. The modified seeds were to be tested to confirm that they would grow and produce high yields of rice with far lower applications of chemical pesticides — exactly the kind of innovation environmental activists should encourage.

Greenpeace has consistently ignored the scientific consensus about the safety of genetically engineered crops, the result of hundreds of risk-assessment experiments, and vast real-world experience. In the United States alone, more than 90 percent of all corn, soy and sugar beets are genetically engineered, and over three decades of consumption of trillions of servings of food from genetically engineered plants around the world, not a single health or environmental problem has been documented.

Image : Greenpeace Greenpeace has variously alleged that the levels of beta-carotene in Golden Rice are too low to be effective or so high that they would be toxic. But feeding trials have shown the rice to be highly effective in preventing VAD, and toxicity is virtually impossible because in vivo conversion of beta-carotene to vitamin A ceases when vitamin A levels in the blood exceed normal.

With no rational basis for its anti-technology activism, Greenpeace has been forced to adopt a "fear, not facts" strategy of trying to scare off the developing nations that are belatedly considering adopting the lifesaving products. In a 2012 screed, Greenpeace claimed, "If introduced on a large scale, golden rice can exacerbate malnutrition and ultimately undermine food security." Psychiatrists call this kind of statement projection: The real threat to the poor and vulnerable is not genetic engineering; it's Greenpeace and its ilk.

Hostility to gene editing in Africa?

This is not the only recent example of hostility toward crops developed with genetic engineering techniques, but we were surprised to encounter a bizarre "Call for Experts in gene editing technology in Africa," from the Network of African Science Academies, Africa Harvest, and CropLife International — "[e]xperts who wish to stand out and be the voice of promoting the gene editing technology in Africa and beyond." The announcement specifies the expertise required to advise about regulating gene-edited crops in Africa — including that applicants must have had "No previous frontline advocacy for or affiliation with Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO) technology." Nowhere in the Call for Experts is there any mention of the converse, which suggests that anyone with a past history of frontline opposition toward GMOs is welcome to apply.

These groups represent a (supposedly) science-based consortium that advises policy and decision makers throughout Africa. Well, they're off to an inauspicious start.

One is left to wonder whether the absurd specification in this advertisement is intentional or else perhaps a Freudian slip. Either way, a negative bias toward new breeding technologies such as gene editing could have dire consequences for African farmers. Using gene editing technologies, scientists are crafting African crops such as maize, banana and cassava to resist pathogens, and to improve yield and resilience in the face of climate change.

Botched study undermines Greenpeace

Another recent and completely clueless anti-technology salvo was a September publication from a group of multi-national "researchers," followed by a press release from Greenpeace EU and a video. In the paper to which they refer, A Real-Time Quantitative PCR Method Specific for Detection and Quantification of the First Commercialized Genome-Edited Plant, the authors claim that they have devised a PCR-based method to distinguish genome-edited plants from plants bred through 'natural' means. According to Greenpeace EU, "The new research refutes claims by the biotech industry and some regulators that new genetically modified (GM) crops engineered with gene editing are indistinguishable from similar, non-GM crops and therefore cannot be regulated." The paper goes on to describe how the methodology was tested on an herbicide-tolerant variety of oilseed rape commercialized by CIBUS, a plant biotechnology company.

Typically, Greenpeace got it completely wrong. According to CIBUS, the varieties tested were in fact developed from spontaneous somaclonal variation, a natural, "non-genetic engineering" method, not from gene editing technology. Euroseeds, a trade association for the seed industry in the EU, further clarifies that the Greenpeace publication actually provides a method to detect a single point-mutation originating from a "mutagenesis method" –another traditional technique that does not involve gene-splicing or gene editing. In other words, the genetic alteration can be detected, but it cannot be determined whether the alteration occurred naturally; through chemical mutagenesis, a venerable but crude technique; or through gene editing. As the Euroseeds article concludes, this is much ado about absolutely nothing.

Ironically, even if the claims in the paper touted by Greenpeace were accurate, they would be an example of "so what" science. The distinction between old and new breeding technologies has never been blurrier, or more meaningless: Except for wild berries and wild mushrooms, virtually all the fruits, vegetables, and grains in our diet have been genetically improved by one technique or another.

Thousands of varieties of currently cultivated crops were created by mutagenesis breeding, a technology that has existed for almost a hundred years. This approach introduces random mutations throughout a plant genome by treatment with harsh chemicals or irradiation. Plants that survive and exhibit desirable new traits can then be propagated from these mutation events into new crop varieties. More than 3,000 varieties of crops have been generated through mutagenesis breeding, according to the Mutant Variety Database, including the popular ruby red grapefruit and barley used for single malt scotch. In addition, "wide cross" hybridizations, which move genes from one species or genus to another in ways that do not occur in nature, have been used to produce crop plants since the 1930s.

One recent advance in conventional plant breeding uses state of the art molecular techniques such as marker assisted selection — an indirect selection process in which a trait of interest is selected based on a marker of some kind that is linked to a trait of interest (e.g. productivity, disease resistance, etc.), rather than on the trait itself.

Molecular genetic engineering to generate transgenic crops (which contain DNA transferred from another organism) involves the very precise introduction of a novel trait into a plant by incorporating genetic material, sometimes from different species, into the plant genome. Bt-brinjal, or eggplant, the insect-resistant variety(ies) adapted by Bangladeshi farmers, is an example of a transgenic crop that has reduced the need for applications of pesticide and increased income and food security.

Gene editing, the most recent molecular genetic engineering technology, does not necessarily involve the introduction of new gene sequences; rather, it may direct only one or a few nucleotide changes within a plant genome. It is an extremely promising new tool for plant breeding, inasmuch as many complex traits such as crop yield, photosynthesis, and drought resistance involve multiple genes, and thus, altering them would be difficult to achieve through conventional breeding alone, or even using transgenic approaches.

The simplicity and ease of gene editing, as well as the fact that it does not (necessarily) add new DNA to the crops themselves, may change the playing field with respect to the regulations that govern "new biotechnology techniques," or NBTs. Plants produced by gene editing more resemble improved versions of breeding mutagenesis, a technology which, unlike transgenesis, is not subjected to extensive regulation in the US or the EU. However, that is, or should be, a distinction without a difference. The method of genetic modification is irrelevant to risk, which should determine the extent and intensity of regulation. In fact, if anything, the precision of the modern molecular techniques and the higher level of characterization of the organisms they produce argue for less regulatory scrutiny, instead of the higher levels that are in place virtually everywhere.

Paradoxically, decades after they should have known better, and disregarding the seamless continuum that exists between old and new technologies, the EU has resolved to over-regulate gene-edited crops under the same draconian, unscientific regulatory paradigm as transgenic crops produced with recombinant DNA technology.

Finally, it is disturbing that an inherently flawed paper cited in a Greenpeace press release can garner significant attention, but it illustrates the power of the anti-science, anti-technology activism that is currently on display. The boundaries between various genetic engineering technologies are becoming increasingly indistinct, as NBTs are mixed and matched to address today's agricultural challenges.

The ability of Greenpeace's "news" to gain traction, added to the anti-Golden Rice "week of protests" in the Philippines and the nonsensical requirements of the "call for gene editing experts" to decide the fate of African farmers, undermine the acceptance of genetically engineered crops around the world. As COVID-19 has disrupted the global food system and delayed the progress of gene edited crops through the gauntlet of unscientific regulation, farmers and others in developing countries, where food security is most tenuous, will bear the brunt of the consequences.

Kathleen Hefferon, Ph.D., teaches microbiology at Cornell University. Find Kathleen on Twitter @KHefferon

Henry Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is a senior fellow at the Pacific Research Institute. He was the founding director of the FDA's Office of Biotechnology. Find Henry on Twitter @henryimiller